The socialization of children is gender-differentiated during early childhood, whether through their environment, the toys offered to them, their families or the staff in educational care settings (Amboulé Abath, 2009). Consequently, children undergo a gender-differentiated educational experience. This section deals with how gendered socialization modulates the characteristics of the children’s connection to learning.

First of all, this translates into differentiated interactions with adults and peers. Adults, parents, grandparents and educators, although they feel they do not act differently with children, change their behaviour depending on a child’s gender. This results in different learning and in different experiences for children. The older the children, the more their peers influence their behaviour.

Nor are the toys, activities and material presented to children free of stereotypes, quite to the contrary. Consequently, they create different gender-dependant learning experiences, encouraging girls to build certain competencies and boys, others.

Learning styles and relationship with educational institutions

Before looking at the differentiated connection to school and learning of Mi’gmaq boys and girls, let’s look at a few context points related to the connection of First Nations to educational institutions. First of all, it is worth repeating that for hundreds of years, among Indigenous peoples, “teachings have been passed on within the context of the family and the community. School has been implemented just over 50 years ago; First Nations’ educational tradition is then quite young and it clashed in many ways with their traditional lifestyle” (Commission de l’éducation, 2007, p. 10). The residential schools, implemented around 1900, as well as all the colonial system, negatively impacted indigenous people’s relationship with educational institutions (Santerre, 2015). We can then say that the connection to education of a majority of indigenous students and their parents, in addition to clashing with their culture (Brabant et al., 2015), is tainted with mistrust. Fortunately, Audy and Gauthier (2019) highlight that according to many researchers, young First Nations members’ connection to school and education is the theatre of a profound change and is becoming a lot more positive, less reactive and resistant.

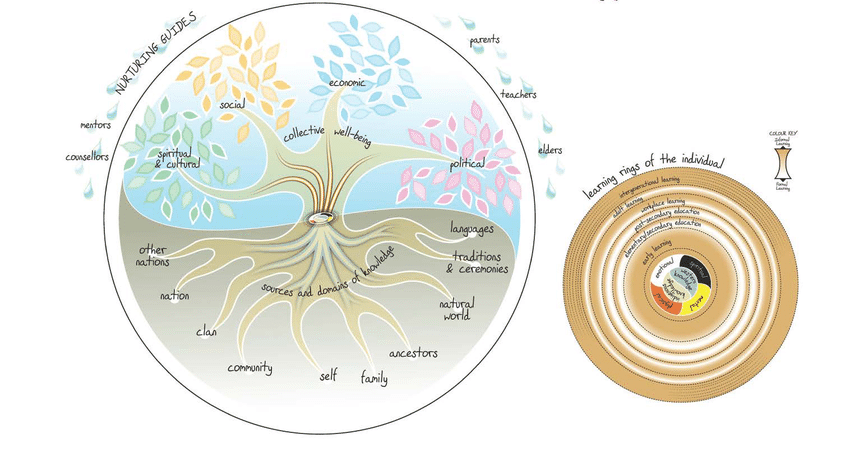

When looking at the connection to learning of young mi’gmaq boys and girls, we have to put aside the accounting view of academic success to adopt a holistic approach (St-Amant, 2003). According to the Canadian Council on Learning (2007), learning from an indigenous perspective is holistic and experiential, it is a lifelong process rooted in Aboriginal languages and cultures, it is spiritually oriented, it is a communal activity, involving family, community and Elders and it is the integration of Aboriginal and Western knowledge. In that sense, the First Nations Holistic Lifelong Learning Model of the Canadian Council on Learning (2009) is a good example of how the connection to learning of many First Nations members isn’t limited to the educational institution itself, but has to be rooted in the community, to touch on many dimensions of the individual and the society, and has to be formal at certain moments, such as during the elementary schooling process, and informal at other times, such as during early childhood.

Figure 2. First Nations Holistic Lifelong Learning Model (Canadian Council on Learning, 2009)

General observations

Interactions with adults and peers

- In terms of motor skills, a little boy who is “not very adept” physically generally receives more negative remarks than a little girl whose motor skills have developed to the same degree. A girl deemed “agitated” is scolded more often than a similarly agitated little boy.

- Adults use girls’ first names less often than boys’ when speaking to children.

- Speakers use a “one-size fits all” type of language as if the entire world were masculine (traditionally, “he”, “him” and “his” were used to refer to both genders).

- References are essentially feminine when it comes to the role of parents in the domestic and nurturing spheres.

- A group of boys is addressed differently from a group of girls (for instance, “hey, big guys” versus “hey, girls”).

- Adults don’t allow boys to express their emotions as fully as they do girls.

- Stereotypes about boys – contending that they are more rational or Cartesian and consequently, more talented than girls in science – and about girls – claiming that they are more emotional, more creative, and therefore superior to boys in art or literature – are highly persistent. These preconceived ideas about the skills of girls and boys can have important implications for their academic confidence and motivation.

- Children play less often with objects typically used by the opposite gender in the presence of a peer, especially when that peer is of the opposite gender.

- The more time girls and boys spend with children of the same gender, the more their behaviour becomes gender-differentiated.

Toys, activities and material

- The toys and clothing parents choose for a child depends more on their baby’s gender than on the child’s spontaneous behaviour.

- By the time they are 20 months old, children have favourite toys typical of their own gender.

- By 2 to 3 years of age, children already have substantial knowledge about stereotypical gender-specific activities, occupations, behaviours and appearances.

- When it comes to material (puppet names, group facilitation tools, characters), the references are primarily masculine.

- Children, especially boys, who engage in activities typical of the opposite gender earn negative feedback from their peers. Activities that receive disapproval are terminated more quickly than those that are positively reinforced.

Observations about girls

Interactions with adults and peers

- Adults sing songs and talk more often to baby girls.

- Emotional states and feelings are discussed more often with girls, increasing their sensitivity to others and fostering the emergence of a more cooperative interaction style in girls’ groups.

- Girls are more often asked to help boys than vice versa.

- They receive more attention from professionals when they are close to the adult (3- to 5-year-olds).

- Professionals interrupt them more often than boys.

- They are asked to be quiet when they are too “talkative”.

- Girls are asked more often to put away the games and toys.

- When there is a conflict between children, adults more frequently ask the girls to be conciliatory.

- Girls are encouraged for their good behaviour.

- Girls are primarily complimented for their attractive appearance.

- They are less often congratulated when they do something well.

- Adults adopt a much broader range of expressions with girls than with boys.

- Parents take care of girls, coddle and mother them, which encourages them to rely more on adults than on themselves.

- When boys interrupt their play, girls react by making proposals for continuing their activity, negotiating, calling for an adult or running away.

- Girls are often the losers when an adult is not there to handle the conflict.

- Girls give way more easily, letting the boys take over their space or whatever they were playing with.

Toys, activities and material

- Toys associated with girls are connected to the fields of care giving, appearance, childcare and sales.

- At the age of 3, the presence of dolls in the activities of girls systematically leads them to reproduce mothering scenes and to develop role playing.

- There are more disguises for girls than for boys.

- The colour pink is particularly for girls.

- Little girls are more often invited to take part in “quiet” activities sitting at a table.

- Girls are supposed to be obedient, docile and orderly, and have fewer choices in terms of their activities.

- Girls mainly engage in activities that are more related to playing pretend and role playing.

- Girls tidy up or offer to tidy up toys even if they haven’t played with them.

- In children’s literature…

- Women appear in secondary roles slightly more often;

- Women and girls are more often shown inside;

- Women are more often depicted in the mother’s role;

- Fewer women hold occupational roles, and there’s not much variety in the occupations they do have, traditional ones at that (education, care giving, sales);

- Women generally have access to only one role, a family role or an occupational role;

- In the private sphere, the mother is most often depicted doing domestic tasks and activities relating to parenting duties (making sure homework is done, giving a bath);

- Girls participate in domestic tasks more often;

- The clothing worn by girls and women is connected to their domestic tasks (apron); and

- Women and girls wear clothing and other items that are exclusively for women (jewellery, hair accessories).

Observations about boys

Interactions with adults and peers

- Adults have more physical interactions with baby boys.

- Fathers prohibit their sons from doing things twice as often as they do their daughters because boys are more likely to handle forbidden objects.

- Boys are punished more often and demonstrate less self-control.

- Boys are called on more frequently than girls.

- Boys generally receive more attention.

- Boys obtain more instructions in response to their questions, which encourages them to become involved in activities (3- to 5-year-olds).

- They speak out and continue to do so longer than girls and occupy more physical and sound space.

- Their unruliness is tolerated more and discouraged less.

- They are encouraged for their good performance.

- They are congratulated and assisted more often.

- Boys receive more encouragement to succeed at a task.

- They receive fewer compliments and, when they do, they are complimented for their physical strength.

- Anger is a more tolerated emotion in boys. In childhood, they primarily learn to express their anger, which could later hinder their ability to communicate.

- Questions asked of boys tend to concern objective information about objects and people (24 to 30 months of age).

Toys, activities and material

- Educators use boys more than girls to test stereotypical toys for boys although no significant difference is observed for neutral and girls’ toys.

- There is a broader range of toys for boys.

- Toys associated with boys include things used in the construction, transportation, technical and scientific fields, to maintain order or wage war and for occupations associated with high social status, such as a physician.

- Construction and interlocking games as well as the technical range LEGOs are part and parcel of boys’ activities. These games, more focussed on the success of the activity, give boys the opportunity to handle objects and explore space.

- At 3 years of age, only boys distinguish between dolls as objects and dolls as toys that represent babies requiring someone to take care of them. They are not as affected as girls by the symbolism of things.

- Little boys are more often invited to participate in motor activities.

- Boys engage more readily in activities involving sand or climbing.

- Boys sometimes interrupt girls’ games by taking over, by destroying their set up or by forcing them to change their scenario.

- Boys have difficulty putting things away; they prefer to go on playing.

- In children’s literature…

- Stories about male heroes are twice as numerous as stories about female heroes;

- Boys are more often illustrated on the cover pages of books;

- Boys’ first names predominate in story titles;

- Boys appear more often than girls in album illustrations;

- Boys and men appear more often in central roles than in secondary roles;

- Boys and men are depicted more often in public places and actively occupied;

- Men are depicted in a greater variety of occupational roles and in some cases are given greater value;

- Men are often depicted as holding two roles: a family role and an occupational role;

- Fathers appear more often in recreational activities involving their children (games, sports, reading) or in quiet moments (reading a newspaper, watching TV).

- Boys play more sports activities;

- Boys argue more and do more foolish things than girls;

- Anger and unruliness are associated more often with boys than with girls;

- Little boys are frequently depicted in an asexual manner; and

- Men are more often depicted in professional accoutrements (wearing glasses).

| Personnages féminins | Personnages masculins | |

|---|---|---|

| Professions | - Sont moins nombreuses à accéder à des rôles professionnels, lesquels restent peu variés et traditionnels (éducation, soins, vente) ;Elles n’ont généralement accès qu’à un seul rôle : familial ou professionnel. | |

References

AMBOULÉ ABATH, Anastasie (2009). Étude qualitative portant sur les rapports égalitaires (garçons et filles) en service de garde, Université Laval, 140 pages.

DUCRET, Véronique and LE ROY, Véronique (2012). La poupée de Timothée et le camion de Lison. Guide d’observation des comportements des professionnel-le-s de la petite enfance envers les filles et les garçons. Le deuxième Observatoire, Genève, 67 pages. Accessible at: http://www.2e-observatoire.com/downloads/livres/brochure14.pdf

FERREZ, Eliane (2006). « Éducation préscolaire : filles et garçons dans les institutions de la petite enfance », Chapter 6, in DAFFLON NOVELLE, Anne, Filles – garçons Socialisation différenciée?, Grenoble: PUG, Vies sociales, 399 pages.

MURCIER, Nicolas (2007). « La réalité de l’égalité entre les sexes à l’épreuve de la garde des jeunes enfants », Mouvements, Volume 1, Number 49, pp. 53 to 62, accessible at: https://www.cairn.info/revue-mouvements-2007-1-page-53.htm

SECRÉTARIAT À LA CONDITION FÉMININE (2018). « Portail Sans stéréotypes », accessible au: http://www.scf.gouv.qc.ca/sansstereotypes/personnel-des-services-de-garde-educatifs/choix-scolaires-et-professionnels/, page accessed on November 12, 2018.

VIDAL, Catherine (2015). Nos cerveaux, tous pareils, tous différents! Laboratoire de l’Égalité, Éditions Belin, 79 pages.