Since the 1990s, a number of studies have shown and confirmed that students who adhere most closely to gender stereotypes are also those who drop out the most (CSE, 1999; Bouchard & St-Amant, 1996; Bouchard, Saint-Amant & Tondreau, 1997). This is an additional angle for understanding the determinants of school perseverance since not only is the learning experience (how the student is treated and trained) modulated by gender, but the relationship to learning is also determined by gender stereotypes (how the student perceives and acts within the school system). Children, from birth, are treated differently in their social environment (family, school, peers and media) according to the gender assigned to them. This adds on top of a differentiated treatment for Mi’gmaq youth because of their racialized (and, moreover, indigenous) identity. Their strengths, difficulties and attitudes are at least partly the result of this differential treatment and their understanding of what it is like to “be a Mi’gmaq girl” or “be a Mi’gmaq boy”. These gender stereotypes, entangled with those associated with being indigenous, will ultimately modulate their aspirations and representations of the future, which in turn will influence their professional orientations (Bouchard, St-Amant, 1997; Plante, Théoret & Favreau, 2010; Potvin & Hasni, 2019; Plante, O’keefe & Théorêt, 2013) and equality between men and women and among all women.

This section further explores how gendered socialization interacts with the relationship to school and learning and with how teachers contribute, usually unconsciously, to the reinforcement of this socialization. By looking at the social realities of boys and girls originating from Mi’gmaq communities, it is, moreover, possible to develop pedagogical approaches that can better meet their respective needs. It should be remembered that while native boys are generally (but not always) more likely to drop out of school, girls do account for a significant proportion of young people who drop out (Dupéré, V. & Lavoie, L, 2018). This proportion is also on the rise, since efforts to combat dropping out in recent years seem to be less effective with girls (Ministère de l’Éducation et de l’Enseignement supérieur, 2015, in Dupéré, V. & Lavoie, L, 2018).

In the first section, we will focus on understanding the link between adherence to gender stereotypes and school perseverance, and then explore the differentiated worlds of boys and girls.

Dominant masculinities and feminities at school

When we look at the relationship to learning, the demands inherited from traditional and dominant masculinities and femininities are considered to be linked to factors affecting disengagement from school (Bouchard & St-Amant: 1996, Bouchard, St-Amant & Tondreau: 1997, Théorêt & Hrimech: 1999). We also notice these traits within young Mi’gmaq of the Gespugwitg, Sugapune’gati, Esge’gewa’gi and Unama’gi districts, currently known as Nova Scotia (McIntyre et coll., 2001).

Behaviours, attitudes, and beliefs inherited from traditional patterns

| Boys | Girls |

|---|---|

| Requirement to demonstrate one's virility to other boys (Jeffrey, 2015) | Strong concern for peer acceptance |

| Transgressions perceived as virile (conflictual relationships with authority, aggressiveness, behavioural disorders, distrust of rules, consumption, etc.) (Dupéré, V. & Lavoie, L, 2018) | The relational dimensions with peers and the adult world play a central role in their equilibrium. |

| Desire for autonomy, which often presents as a difficulty to communicate and ask for help | Calm, listening and discretion are generally perceived as feminine traits, which can mask their problems (Eurydice, 2010). |

| Model of the male provider (Théorêt & Hrimech, 1999) | Relationship model (Théorêt & Hrimech, 1999) Girls place a lot of energy and importance on their relationships with peers and adults, including peer acceptance. |

| Lower value placed on academic achievement, effort and graduation | Higher value placed on academic achievement, effort, and graduation |

| Competition and injunctions to be “the best”, resulting in a good self-esteem and an often overestimation of one’s abilities (McIntyre et al., 2001) | Injunction to be submissive and not take too much space, resulting in low self-esteem and an underestimation of one’s abilities (McIntyre et al., 2001) |

Young people who drop out also have undifferentiated motivations. Think of the poverty, unfortunately very prevalent in the indigenous population, lack of family support, academic failure and discouragement (Barribeault, 2016) that are equally common justifications for both genders. On the other hand, boys’ and girls’ school dropout trajectories also show notable differences, in both native and non-native people (McIntyre et al., 2001, 2003; Perron & Côté, 2015), which are related to the behaviours, attitudes and beliefs presented in the above table.

Factors cited as motivating boys and girls to drop out of school

| Boys | Girls |

|---|---|

| The desire or need to work (Perron & Côté, 2015; Raymond 2008) | Frailties in relational dimensions (Raby, 2014) |

| Conflicts with teachers, suspensions and expulsions related to behavioural difficulties (Lessard, 2004; McIntyre et al., 2001)) | Family adversity (lack of parental support, violence, judicialised behaviours of parents, family responsibilities, etc.) (Raby, 2014; McIntyre et al., 2001) |

| More often say they don't like school (Lessard, 2004; Perron & Côté, 2015) | Psychological distress and mental health problems (Enquête québécoise sur la santé des jeunes au secondaire, 2010-2011) |

| More problems externalised (RRM, 2018) | More problems internalised (RRM, 2018) |

| Frustrations related to school work (McIntyre et al., 2001) | Pregnancy (McIntyre et al., 2001) or family responsibilities (Perron & Côté, 2015) |

We observe here that boys more often justify their dropping out of school as being due to an interest in work, a rejection of the school world and externalised behavioural issues. Conversely, the reasons given by girls are connected to the personal, relational and psychological spheres. These differences are clearly related to the behaviours, attitudes and values inherited from dominant gender models. Not only do boys adhere more to gender stereotypes than girls, but the norms, values and models related to these gender stereotypes create more distance and conflict with the school world. Nevertheless, these differences remind us of the importance of taking into account the academic difficulties of girls, which are more often internalised and therefore harder to see.

Parents’ schooling and social class

In general, the achievement gap between girls and boys is smaller than that between students from different socio-economic backgrounds (CSE, 2005). Academic achievement is strongly correlated with students’ social backgrounds from a socio-economic perspective. This is partly related to the under-education of mothers, which is known to have an impact on their children’s first diploma: students whose mothers have no diploma or little schooling are more at risk of dropping out of school than others (Fédération autonome de l’enseignement [FAE] & Relais-femmes, 2015). In indigenous communities, family traits also have an impact on academic perseverance. Indeed, having a parent with at least a high school diploma in hand is related to graduating from high school, as having one or more siblings who dropped out of school is linked to high school dropout (Perron & Côté, 2015). The gap between boys’ and girls’ school dropout rates is smaller in privileged environments because socio-economic background has a greater effect on boys’ success than on that of girls (Ministère de l’Éducation, du Loisir et du Sport, 2005). Some authors put forward the explanation that boys from more advantaged backgrounds adhere less to gender stereotypes, which is consistent with the fact that parental education seems to be a protective factor (Bouchard & St-Amant, 1996). Indeed, children whose parents are highly educated are less likely to identify with gender stereotypes. The most vulnerable children have more stereotyped behaviours, which reinforces their vulnerability (RRM, 2016).

The stereotype threat

One of the important phenomena in explaining the role of gender stereotypes in educational success is the stereotype threat. This concept has been widely used to understand the effect of stereotypes on learning among stigmatized individuals (black students, seniors, women, etc.). Several research studies have shown that evoking a stereotype can, unconsciously, have an impact on the performance of the people targeted by the stereotype in question. For example, simply referring to the gender of students before a math exam has an effect on the performance of girls (Kinch, 2017). Thus, there is no need to refer directly to the gender stereotype positing that boys are naturally better at mathematics than girls for there to be an effect. This highlights the unconscious aspect of the role gender and racial stereotypes play in learning dynamics.

When students are required to answer questionnaires to measure adherence to gender stereotypes, it turns out that young people in our schools today explicitly adhere less to gender stereotypes than before. However, we note that in assessment or learning situations, gender stereotypes connected to different school subjects (mathematics, science, language) still have an impact on student performance (Plante, Théorêt & Favreau, 2010). The literature on this phenomenon identifies effects on self-esteem, on students’ perceptions of their own abilities (Potvin & Hasni, 2019) as well as on the value placed on learning (Plante, Théorêt & Favreau, 2010). In the long term, these stereotypes have a predictive effect on academic success, pathways and orientation that reflect gendered trajectories (Plante, Théorêt & Favreau, 2010, Rouyer, Mieyaa & Le Blanc, 2017). These findings point to the importance of deconstructing the idea that certain disciplines are more accessible to boys or girls. Besides, Getty (2013) underlines that young Mi’gmaq boys face negative stereotypes because of their ethnic identity, in addition to gender stereotypes.

Relationship to learning and school

In addition to the differentiated connection to school and learning of Mi’gmaw boys and girls, let’s a few context points related to the connection of First Nations to school as an institution must be put in light. First of all, it is worth repeating that for hundreds of years, among Indigenous peoples, teachings have been passed on within the context of the family and the community. School has been implemented just over 50 years ago; First Nations’ educational tradition is then quite young and it clashed in many ways with their traditional lifestyle (Commission de l’éducation, 2007, p. 10). The residential schools, implemented around 1900, as well as all the colonial system, negatively impacted indigenous people’s relationship with educational institutions (Santerre, 2015). In addition to the residential schools, there were, in Mi’gmaq communities of Gespeg’ewa’gi, “reserve schools”, which had similar assimilation goals (Trenholm, 2019). We can then say that for a majority of indigenous students and their parents, school clashes with their culture (Brabant et al., 2015) and their connection to it is tainted with mistrust. Fortunately, Audy and Gauthier (2019) highlight that according to many researchers, young First Nations members’ connection to school and education is the theatre of a profound change and is becoming a lot more positive, less reactive and resistant.

According to the Canadian Council on Learning (2007), learning from an indigenous perspective is holistic and experiential, it is a lifelong process rooted in Aboriginal languages and cultures, it is spiritually oriented, it is a communal activity, involving family, community and Elders and it integrates Aboriginal and Western knowledge. Yet, Mi’gmaq students’ journey into high school mainly takes place in a non-native setting, where the relationship to learning is different. Minde and Minde (1995) note, among others, the fact that non-interference, i.e. letting the child learn at his or her own pace, without interfering in their learning process by telling them what to learn and in which order, is a cultural norm of many First Nations that haven’t been understood yet by the main school systems of North America, and that this misunderstanding contributed to the young First Nations students’ lack of self-esteem and to their subsequent academic failure. As explained by McIntyre et al. (2001, p. 19),

traditional Aboriginal way of teaching children self-reliance was not through physical or verbal coercion but through modelling. Traditionally, children were responsible for their own learning. They learned through watching their family members complete certain tasks. Very rarely was a child spoken to, in the modelling process. Thus they were not told to complete routines. Demands were not made, limits were not set, and punishments were regarded as inappropriate. With the weakening of the family unit as the primary socializing agent, Aboriginal children have not received the acceptable level of “interference” from families in order to learn that showing up for school on time and completing homework on time, and so on, are now required. Again, teachers and various school officials may misinterpret Aboriginal children and youth’s lack of performance in school as laziness (Minde & Minde, 1995).

Perceptions of school perseverance and academic success

It is also important to underline a few elements related to the perceptions of school perseverance and academic success among First Nations, even though it can vary from one Nation to another and from one person to another. If, in the European-inspired educational system, academic success is measured with grades, it is often the other way round in indigenous communities, where the survival of the culture and the language is equally important (Commission de l’éducation, 2007). For the Innu, for example, academic success is defined by parents, students and teachers more in terms of perseverance and of capacity to put in enough efforts to get passing grades. The notion of perseverance then becomes an important dimension of academic success (Commission de l’éducation, 2007, p. 11). For the Inuit, ancient know-how that supports traditional lifestyles, such as knowing how to survive in tundra, is equally important (Commission de l’éducation, 2007). Within the Innu community of Mashteuiash, it is assumed that academic success is a collective responsibility and that it is by taking into account all dimensions of the Human Being that we achieve good health, a pride feeling and academic success. The Pekuakamiulnuatsh have a global and holistic vision of the present time and the future, and they make sure to foster the spiritual, emotional, mental and physical fulfillment of everyone (Girard & Vallet, 2015, p. 27). Consequently, when looking at the connection to learning of young Mi’gmaw boys and girls, we have to put aside the accounting view of academic success to adopt a holistic approach (St-Amant, 2003), while being open and sensitive to all various students’ walks of life.

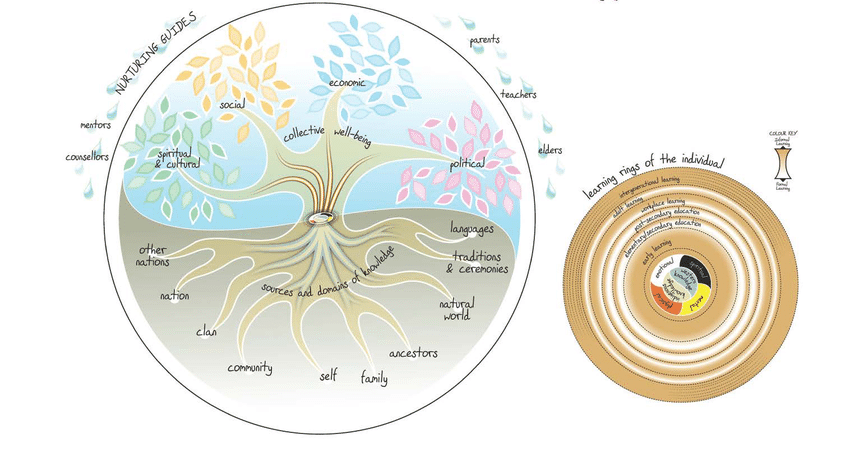

In that sense, the First Nations Holistic Lifelong Learning Model of the Canadian Council on Learning (2009) is a good example of how the connection to learning of many First Nations members isn’t limited to the educational institution itself, but has to be rooted in the community, to touch on many dimensions of the individual and the society, and has to be formal at certain moments, such as during the secondary schooling process, and informal at other times, such as during early childhood.

Figure 2. First Nations Holistic Lifelong Learning Model (Canadian Council on Learning, 2009)

The school as a place where gender and racial stereotypes are reproduced

We saw in the previous section that gender stereotypes affect students’ relationships to learning. However, it is equally important to understand that the school is also a place where gender stereotypes are reproduced. The content conveyed (curriculum and textbooks) and educational practices (interactions with the school team) have the effect of reinforcing the values, behaviours, ideas and models that are traditionally associated with the worlds of women and menmen inherited from colonization (CSF, 2016; Getty, 2013).

Despite many improvements in the last decades, the curriculum and textbooks in Quebec still tend to mask the contributions of women and First Nations and Inuit people (Bories-Sawala, 2019). In history, for example, certain notions have been added to highlight feminist struggles. If, before the review of the program in 2017, there was little or no discussion of “their exclusion or their political action, the legal inequalities they suffer or their socio-economic contributions” (CSF, 2016), today’s prescribed concepts take a little more into account the exclusion of women and the wins of the feminist movement in its quest for equality (Gouvernement du Québec, 2017). An in-depth feminist analysis of the new textbooks would be needed in order to understand which improvements were made. In terms of textbook choices, highlighting women’s contribution to history and explaining the causes of their absence is optional when it comes to choosing the textbooks used by Quebec schools (CSF, 2016). These practices may suggest that equality between men and women has been achieved. Finally, according to the historian Helga E. Bories-Sawala, textbooks have greatly improved over the last years in terms of indigenous history, but a whole history chapter is missing, as First Nations and Inuit disappear around the 18th and 19th centuries, and then awkwardly come back in the middle of the 20th century with the Aboriginal comeback, making us wonder what they have been all this time (Altéresco, 2015). This invisibilization helps reinforce the stereotypes associated with Mi’gmaq boys and girls.

At the same time, interactions with members of the school team also contribute to reinforcing gender stereotypes and those associated with the fact of being indigenous. On the one hand, teachers (like other adults) tend to perceive boys and girls differently, and on the other hand, they tend to have different expectations and act differently depending on the gender and the ethnic identity of their students. The fact that teachers’ perceptions are tainted by gender stereotypes is fairly well documented (Duru-Bellat, 2010, Solar, 2018). In 2016, the Conseil du statut de la femme (CSF, 2016) published a survey that told us that:

- 76% of Quebec teachers believe that boys naturally prefer activities that mobilize technical and mathematical skills;

- 73% are convinced that girls apply themselves more and are more disciplined; and

- 72% believe that students have distinct learning styles based on their gender.

This difference in perceptions has an unintended but obvious effect on what is expected of students (Solar, 2018). For instance, teachers often have higher expectations in mathematics for boys, while girls are expected to work more carefully (Solar, 2018). Ultimately, these expectations present as teaching practices that are adapted not to the student’s gender, but to gender stereotypes (Duru-Bellat, 2010). The expectations towards Mi’gmaq students, girls and boys, are also lower and different from the ones teachers have towards non-native students: we expect them to have lower results (Getty, 2013; McIntyre, 2001). These perception biases add up to the marginalization and the exclusion of Mi’gmaq students “by the racist conduct of their peer groups (Beckett, 2003), their teachers, and the oppressive educational system that expects them to do poorly” (Getty, 2013, p. 57).

Considering that teachers’ expectations and perceptions tend to pull students’ results up or down (Pygmalion effect and Golem effect), gender stereotypes may here have the effect of a “self-fulfilling prophecy in terms of the interactions and assessments conducted in a school context”, which in turn feeds into the beliefs that students hold about their own abilities (Levasseur & de Tilly-Dion, 2018). Thus, the sense of competence and the self-esteem of Mi’gmaq students is dependent on their gender and their experience of racism.

To sum up, the effect of gender stereotypes on the relationship to learning and the differences in boys’ and girls’ school experiences are related to their academic performance and career orientation. Understanding these differences thoroughly allows us to see the consequences of differentiated socialization and to begin to reflect on our behaviours towards young people. The following findings are drawn from various studies on the subject and represent observed trends and not absolute facts about boys and girls. Moreover, as many studies have been conducted in non-native contexts, when it isn’t specified that a finding is drawn from an inquiry in a native context, it must be assumed that it was retrieved from a non-native context. Some nuances can exist, but to our knowledge, they haven’t been formally documented yet. Individual adolescents adhere more or less strongly to the multiple stereotypes associated with their gender and their ethnic identity.

General observations

Interactions with adults and peers

- Members of school teams perceive students’ difficulties differently. In blind tests, in the case of files bearing a female name, difficulties are perceived as being related to the student’s general understanding. For files bearing a male name, the same difficulties are perceived as being related to the student’s behaviour.

- Physical, athletic or cultural activities are fundamental to several elements related to educational success, including development, well-being, self-esteem and fulfillment of young people. However, the provision of activities often differs according to gender: for example, physical and sport activities are more often offered to boys and arts and socio-cultural activities to girls. One of the consequences of this is that from the age of 12 onwards, girls gradually decrease the practice of sports and leisure activities, while boys remain more active than girls, regardless of their age group.

- School textbooks still present a stereotypical view of men and women as well as First Nations and Inuit, and mask certain gender inequalities.

- Boys are most often questioned when new notions are introduced, while girls are mostly questioned at the end of the session.

- When it comes to evaluation, girls receive more comments and congratulations regarding form (good writing, careful presentation, good conduct, work) while the boys receive proportionally more feedback related to content and performance (skill, intelligence, gift, creativity).

- Girls’ difficulties are commented on as being related to more cognitive considerations, and feedback insists on a return to basics, with concern being expressed about the student’s general understanding, whereas these same difficulties are perceived, in the case of boys, as being more punctual, mainly related to their behaviour.

- Boys are slightly more likely than girls to experience conflictual relationships with their teachers, while girls are more likely to have friendly relationships with the teaching staff (Chouinard, Bergeron, Vezeau & Janosz, 2010).

Relationship to school and learning

- For girls, the choice to engage in physical activity or sport is primarily motivated by the feeling of belonging to a group or social network, whereas for boys, it is primarily a desire to perform.

- On average, girls place more value on graduation than do boys.

- Boys have a higher sense of competence in mathematics while girls generally have a higher sense of competence in French/English (Chouinard, Bergeron, Vezeau & Janosz, 2010).

- Girls are slightly more likely than boys to report an interest in languages and mathematics (Chouinard, Bergeron, Vezeau & Janosz, 2010).

- Both boys and girls consider language-related domains to be more suitable for girls (Plante et al., 2019).

- A number of media-based models associate body image and being sexy with being popular with peers. This desire to be popular is not new, but “it now seems to be more associated with a sexual attitude” (Duquet, 2013).

Observations concerning girls

Interactions with adults and peers

- They tend to be evaluated in terms of form (good handwriting, neat presentation, good conduct, work).

- Girls’ relational and academic difficulties are often ignored because they are linked to internalized behaviours, which are not very visible if they are not paid attention to. They are more invisible in the classroom and submissive when it comes to authority (Dupéré, V. & Lavoie, L, 2018).

- Girls’ academic difficulties are generally underestimated by school staff compared to those of boys.

- Girls like to pass on their knowledge to younger children.

- Girls value their friends at school and often discuss with them all matters related to the school environment.

- Girls are more often asked closed questions, and their questions remain unanswered more often.

- Girls are highly motivated by the goal of acceptance (by the teacher and the peer group).

- Girls receive praise from their teachers for both behaviour and academic performance: it would appear that they are calm, dynamic, disciplined, although sometimes talkative, in keeping with female stereotypes.

- The segregation and stereotypes that girls are targeted by lead them to adopt behaviours of resistance by seeking out coalitions within their gender category (Gagnon, 1999).

- Girls are more solicited than boys when it comes to helping students in difficulty or assisting the teacher, which reinforces the stereotype of girls being responsible for the care and well-being of others.

- The reasons for punishment most often associated with girls are: tardiness in work, chatting, cell phones and smoking.

- Girls are punished less often than boys.

- In math and science, girls are more sensitive to the supportive atmosphere exhibited by the teacher.

- Girls are more often victims of sexual, verbal or physical violence (Dupéré, V. & Lavoie, L, 2018).

Relationship to school and learning

- Girls are calmer and less impulsive than boys and are more compliant with rules and instructions.

- Girls generally have a positive relationship with school: they like school, feel good about it, and take it seriously.

- Girls have a concept of learning that relates to the self-actualization: learning enables them to project themselves into the future and to value themselves.

- Girls are more involved in their interpersonal relationships.

- Between the ages of 15 and 18, rates of depression increase significantly for both boys and girls. Nevertheless, rates of depression in girls are up to twice as high as those observed in boys. The higher rates of depression are found within First Nations teenagers, especially young First Nations girls, who suffer the most from depression (McIntyre et coll., 2001). Depressive episodes are one of the reasons girls give for dropping out of school (Meunier-Dubé & Marcotte).

- Girls experience more anxiety related to schoolwork regardless of their socio-economic background. They experience a lot of stress during exam periods.

- The reasons given by girls for dropping out are more discrete.

- They are more likely to perceive the juvenile (young people’s social and cultural world) and school worlds as coexisting side by side.

- They perceive the benefits of the subjects taught and more often like the subjects in which they have difficulties.

- Girls attribute their poor academic performance more to intrinsic factors.

- Girls have higher career aspirations than boys: their career choices require longer schooling, most often at university.

- In scientific pathways, girls seem to prefer biology to physics and chemistry (Potvin & Hasni, 2019).

- The consequences of dropping out of school are more severe for girls. They are at a greater disadvantage, particularly from an economic point of view. In 2012, 41.2% of women who had not graduated from high school had an employment income of less than $20,000 despite full-time employment (RRM, 2016).

Observations concerning boys

Interactions with adults and peers

- Boys receive more attention than girls (encouragement, criticism, listening) and receive increased attention when unruly. They tend to have more teacher-focused interactions and more individualized instruction (Duru-Bellat, 2010).

- They are evaluated more in terms of content and performance (ability, intelligence, gift, creativity).

- Boys are more likely to tolerate the rough draft aspect of a job, which reduces the need for them to refine the presentation or structure of their work and evaluations.

- Teachers often expect boys to have a greater mastery of content, especially in math and science.

- Boys receive more attention in mathematics.

- Boys who perform well and have a positive relationship at school are at greater risk of social exclusion and bullying because they do not fit into the boys’ group culture.

- The aggressiveness component associated with factors that can precipitate their dropping out (conflict with authority and academic failure) makes the riskiness of their situations much more obvious to those around them.

- Boys are asked to perform more physical tasks.

- They are punished more often than girls.

- The most common grounds for punishment for boys are: lack of discipline, insolence, incivility, degradation, and violence.

- Transgression of rules is perceived as a manly attitude that may be encouraged in boys who seek to prove their masculinity to their peers.

Relationship to school and learning

- Some boys have a real aversion to school combined with a much stronger attraction to leisure activities and paid work.

- Paid work is, already at this age, more interesting for boys who, even in informal work, earn on average $3 per hour more than girls (La Presse, 2020). Quite quickly, the latter are able to find jobs that pay more than the minimum wage.

- Some boys reject the values associated with school.

- Boys have vaguer career and post-secondary educational aspirations and experience more indecision in this regard. This is a determinant of persistence, since aspirations can give meaning to the learning process.

- Boys perceive slightly more advantages to dropping out of school than girls. (Chouinard, Bergeron, Vezeau and Janosz, 2010)

- Boys are more likely to lower the impact of their academic performance on their future.

- Boys, on average, have lower expectations and place less value on different subjects, which would appear to reduce their motivation and investment of time and energy.

- Boys value effort less in the school setting.

- Adherence to the value of academic achievement is less evident for many boys.

- For many boys, reading and language are associated with the feminine world.

- Boys have a high level of overall self-efficacy, especially in grades 9 and 10.

- Certain social norms encourage boys to be less engaged in school. For example, it is less accepted to show a high interest in school work, which may be perceived as a feminine attitude.

- Boys attribute their poor academic performance more to extrinsic factors.

- Play culture, which may conflict with the school world, is more prevalent among boys.

- For many boys, it is very difficult to reconcile school experiences with their lives outside of school.

- It appears that attention to boys’ inappropriate behaviours and the promotion of male stereotypes leads boys to drop out of school more often than girls.

References

Barribault, L. (2016). Le décrochage scolaire chez les filles : un phénomène sous-estimé? Rire: Réseau d’information sur la réussite éducative. Page consultée le 26 août 2020.

Brabant, C., Croteau, M., Kistabish, J. et Dumond, M. (2015). « À la recherche d’un modèle d’organisation pédagogique pour la réussite éducative des jeunes et des communautés des Premières Nations du Québec : points de vue d’étudiants en administration scolaire », Revue de la persévérance et de la réussite scolaires chez les Premiers Peuples, Vol. 1, pp. 29-34.

Canadian Council on Learning (2007). Redefining How Success is Measured in First Nations, Inuit and Métis Learning, Report on Learning in Canada 2007 (Ottawa: 2007). 47 pages.

Canadian Council on Learning (2009). The State of Aboriginal Learning in Canada: A Holistic Approach to Measuring Success, (Ottawa: 2009). 77 pages.

Chouinard, R, Bergeron, J, Vezeau, C et Janosz, M. (2010). « Motivation et adaptation psychosociale des élèves du secondaire selon la localisation socioéconomique de leur école », Revue des sciences de l’éducation, 36 (2), pp. 321-342.

Commission de l’Éducation (2007). Mandat d’initiative : La réussite scolaire des Autochtones – Rapport et recommandations, février 2007, Bibliothèque et archives nationales du Québec, 68 pages.

Conseil du statut de la femme (2016). Avis: L’égalité des sexes en milieu scolaire. Québec, Gouvernement du Québec, 154 pages.

Duquet, F. (2013). L’hypersexualisation sociale et les jeunes, Cerveau & Psycho, L’Essentiel n° 15, pp 38-45.

Duru-Bellat, M. (2010). Ce que la mixité fait aux élèves. Revue de l’OFCE, 114(3), 197-212.

EURYDICE, 2010, Différences entre les genres en matière de réussite scolaire: étude sur les mesures prises et la situation actuelle en Europe, Commission Européenne: Bruxelles, 142 pages.

Gagnon, C. (1999). Pour réussir dès le primaire : filles et garçons face à l’école, Les Éditions du remue-ménage, Montréal, 173 pages.

Girard, J. et Vallet, M. (2015). « La réussite éducative : les solutions au-delà de l’école », Revue de la persévérance et de la réussite scolaires chez les Premiers Peuples, Vol. 1, pp. 26-28.

Jaegers, D. & Lafontaine, D. (2018). Perceptions par les élèves du climat de soutien en mathématiques : validation d’échelles et étude des différences selon le genre en 5e secondaire. Mesure et évaluation en éducation, 41 (2), 97–130.

Jeffrey, D. (2016). «Identité masculine et épreuves de virilisation à l’adolescence». Educere et Educare.

Kinch, Simon-Benoît. (2017). « L’effet de la menace du stéréotype sur le rendement des élèves en orthographe » Mémoire. Montréal (Québec, Canada), Université du Québec à Montréal, Maîtrise en éducation.

Lessard, Anne. (2004). «Le genre et l’abandon scolaire», Mémoire. Sherbrooke (Québec, Canada), Université de Sherbrooke, Maîtrise en éducation.

Levasseur, C, de Tilly-Dion L. (2018) La mixité de genre en éducation: quelques implications des contextes éducatifs non mixtes pour la réussite scolaire et sociale des élèves, Rapport préparé dans le cadre de la Conférence de consensus sur la mixité sociale et scolaire tenue par le Centre de transfert pour la réussite éducative du Québec (CTREQ) les 9 et 10 octobre 2018.

McIntyre, L., Wien, F., Ruddherham, S., Etter, L., Moore, C., MacDonald, N., Johnson, S & Gottschall, A. (2001). An Exploration of the Stress Experience of Mi’kmaq On-Reserve Female Youth in Nova Scotia, Maritime Centre of Excellence for Women’s Health. https://cdn.dal.ca/content/dam/dalhousie/pdf/diff/ace-women-health/ACEWH_stress_mikmaq_on_reserve_female_youth_NS.pdf

McIntyre, L., Wien, F., Rudderham, S., Etter, L., Moore, C., MacDonald, N., Johnson, S. et Gottschall, A. (2003). “A Gender Analysis of the Stress Experience of Young Mi’kmaq Women”, Centre of Excellence for Women’s Health Research Bulletin, 4(1), 7–10. http://www.cwhn.ca/sites/default/files/PDF/CEWH/RB/bulletin-vol4no1EN.pdf

Meilleur, C. (2020). Biais cognitifs en éducation : l’effet Pygmalion, Knowledge One. Page consultée le 10 septembre 2020.

Meunier-Dubé, A, Marcotte, D. Les difficultés de la transition secondaire-collégiale : quand la dépression s’en mêle, Rire: Réseau d’information sur la réussite éducative. Page consultée le 28 août 2020.

Minde, R. et Minde, K. (1995). « Socio-Cultural Determinants of Psychiatric Symptomatology in James Bay Cree Children and Adolescents », The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 40(6), 304-312. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/070674379504000605?journalCode=cpab

Perron, M. et Côté, É. (2015). « Mobiliser les communautés pour la persévérance scolaire : du diagnostic à l’action », Revue de la persévérance et de la réussite scolaires chez les Premiers Peuples, 1, 12-16. http://colloques.uqac.ca/prscpp/files/2015/01/Revue-PRSCPP-vol.-1.pdf

Pinette, S. et Guillemette, S. (2016). « La reconnaissance culturelle innue au sein d’une école primaire », Revue de la persévérance et de la réussite scolaires chez les Premiers Peuples, 2, 18-21.

Plante, I., Théorêt, M. & Favreau, O. E. (2010). Les stéréotypes de genre en mathématiques et en langues : recension critique en regard de la réussite scolaire. Revue des sciences de l’éducation, 36 (2), 389–419.

Plante, I., O’Keefe, P.A., Aronson, J. et al. (2019). The interest gap: how gender stereotype endorsement about abilities predicts differences in academic interests. Soc Psychol Educ (22), 227–245.

Potvin, P, et Hasni, A. (2019). Les jeunes filles et la science, Acfas Magazine, Université du Québec à Montréal, Université de Sherbrooke.

Raby, J. (2014). Raccrocher de toutes ses forces: Analyse exploratoire du décrochage et du raccrochage scolaire des femmes au Centre-du-Québec, 120 pages.

Raymond, Mélanie, (2008). Décrocheurs du secondaire retournant à l’école, Division de la culture, tourisme et centre de la statistique de l’éducation, Ottawa, Gouvernement du Canada, 2008.

Réseau Réussite Montréal. (2016) Pour une égalité filles-garçons en persévérance scolaire,Page consultée le 12 novembre 2020.

Réseau Réussite Montréal. (2018). Lecture et persévérance scolaire, Page consultée le 13 juillet 2020.

Secrétariat à la condition féminine. (2018). «Comment agir», Portail SansStéréotypes, article consulté le 12 septembre 2020, http://www.scf.gouv.qc.ca/sansstereotypes/comment-agir/ce-qui-est-propose/

Simard, V. (2020). L’iniquité salariale dès l’adolescence ? La Presse, Article consulté le 12 novembre 2020.

Solar, C. (2018). Nous devons élever nos filles et nos fils autrement, les conférences du consensus, 10 octobre 2018.

Théorêt, M., & Hrimech, M. (1999). Les paradoxes de l’abandon scolaire : trajectoires de filles et de garçons du secondaire. Canadian Journal of Education/Revue Canadienne de l’éducation, 24(3), 251–264.

Trépanier, M. (2014).Redéfinition des rôles de genre et diversité des stratégies d’adaptation :des défis posés à l’intervention, Présentation Powerpoint présentée le 16 octobre 2014.

Sylliboy, J. (2017). Two-spirits: Conceptualization in a L’nuwey Worldview, Mount Saint Vincent University, 113 pages.

Wilkins D. F. (2017). « Why Public Schools Fail First Nation Students », Antistatis, 7(1), 89-103. https://journals.lib.unb.ca/index.php/antistasis/article/view/25151