Although the socialisation of children becomes gender-differentiated well before their arrival at primary school, it does not stop there. On the contrary, it continues and even becomes more accentuated as children contend with an educational experience that differs depending on their gender (Gagnon, 1999). This section deals with the ways in which gendered socialisation modulates the characteristics of the children’s connection to learning.

First of all, gendered socialisation translates into in differentiated interactions with adults and peers. Adults, parents and educators, although they feel they do not act differently with children, change their behaviour depending on a child’s gender. This results in different learning and in different experiences for children. The older the children, the greater the influence their peers have on their behaviour.

These differentiated interactions lead children to develop learning styles and a relationship with school that differ according to gender. A thorough understanding of these differences makes it possible to see the consequences of differentiated socialisation and to start thinking about our own behaviours with children.

Learning styles and relationship with school

Before looking at the differentiated connection to school and learning of mi’gmaw boys and girls, let’s look at a few context points related to the connection of First Nations to school as an institution. First of all, it is worth repeating that for hundreds of years, among Indigenous peoples, “teachings have been passed on within the context of the family and the community. School has been implemented just over 50 years ago; First Nations’ educational tradition is then quite young and it clashed in many ways with their traditional lifestyle” (Commission de l’éducation, 2007, p. 10). The residential schools, implemented around 1900, as well as all the colonial system, negatively impacted indigenous peoples’ relationship with educational institutions (Santerre, 2015). We can then say that the connection to school of a majority of indigenous students and their parents, in addition to clashing with their culture (Brabant et al., 2015), is tainted with mistrust. Fortunately, Audy et Gauthier (2019) highlight that according to many researchers, young First Nations members’ connection to school and education is the theater of a profound change and is becoming a lot more positive, less reactive and resistant.

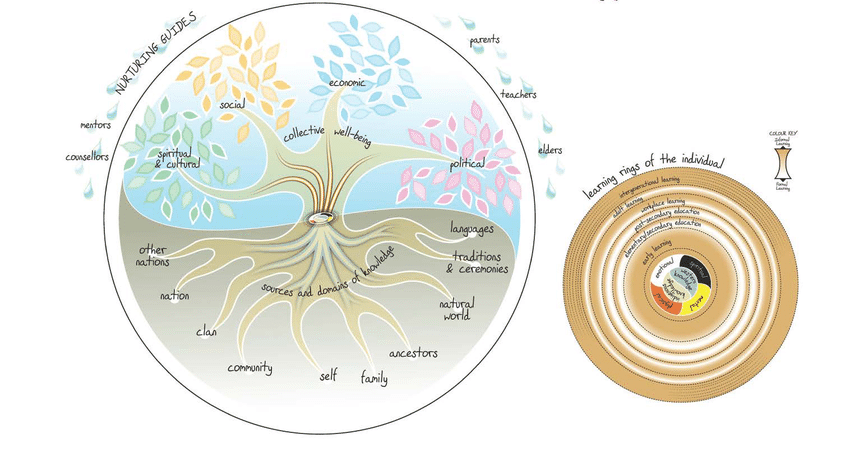

According to the Canadian Council on Learning (2007), learning from an indigenous perspective is holistic and experiential, it is a lifelong process rooted in Aboriginal languages and cultures, it is spiritually oriented, it is a communal activity, involving family, community and Elders and it is an integration of Aboriginal and Western knowledge.

Perceptions of school perseverance and academic success

It is also important to underline a few elements related to the perceptions of school perseverance and achievement among First Nations, even though it can vary from one Nation to another and from one person to another. If, in the european-inspired educational system, academic success is measured with grades, it is often the other way round in indigenous communities, where the survival of the culture and the language is equally important (Commission de l’éducation, 2007). For the Innu, for example, “academic success is defined by parents, students and teachers more in terms of perseverance and of capacity to put in enough efforts to get passing grades. The notion of perseverance then becomes an important dimension of academic success.” (Commission de l’éducation, 2007, p. 11). For the Inuit, ancient know-how that supports traditional lifestyles, such as knowing how to survive in tundra, is equally important (Commission de l’éducation, 2007). Within the Innu community of Mashteuiash, it is assumed that academic success is a collective responsibility and that it is by “taking into account all dimensions of the Human Being that we achieve good health, a pride feeling and academic success. The Pekuakamiulnuatsh have a global and holistic vision of the present time and the future, and they make sure to foster the spiritual, emotional, mental and physical fulfillment of everyone” (Girard et Vallet, 2015, p. 27). Consequently, when looking at the connection to learning of young mi’gmaw boys and girls, we have to put aside the accounting view of academic success to adopt an holistic approach (St-Amant, 2003).

In that sense, the First Nations Holistic Lifelong Learning Model of the Canadian Council on Learning (2009) is a good example of how the connection to learning of many First Nations members isn’t limited to the educational institution itself, but has to be rooted in the community, to touch on many dimensions of the individual and the society, and has to be formal at certain moments, such as during the elementary schooling process, and informal at other times, such as during early childhood.

Figure 2. First Nations Holistic Lifelong Learning Model (Canadian Council on Learning, 2009)

The following observations are drawn from various studies on the subject and represent observed trends mainly in non-indigenous contexts (Conseil du statut de la femme, 2016; Epiney, 2013; Gagnon, 1999; Secrétariat à la condition féminine, 2019), as very few studies have been done on this topic (Davison et al, 2004; Saint-Amant, 2003; Sylliboy, 2017). They are not absolute facts about boys and girls. Individual children adhere more or less markedly to the multiple stereotypes associated with their sex.

General observations

Interactions with adults and peers

- Girls are generally more open to fraternising with boys than vice versa.

- Girls are clearly rejected in sports by boys, particularly during recess.

- Most pupils, girls and boys, prefer mixed classes at school.

- A number of media models associate body image and being sexy with being popular with one’s peers. This desire to be popular is not new, but today there seems to be a closer association with sexuality.

- Boys are encouraged more to play with trucks by their parents and girls, with dolls.

- The toys parents buy for their boys and girls are not the same colour.

- Parents are more abrupt with their sons and gentler with their daughters.

- Parents interpret the reactions of their daughters and sons differently (for instance, a girl who cries is sad whereas a boy who cries is angry).

Learning styles and relationship with school

- Textbooks today continue to present stereotyped views of men and women, as well as of indigenous men and women, and still render invisible certain inequalities between women and men and between native and non-native women.

- Boys are questioned more often when new concepts are introduced while girls are questioned primarily at the end of a class.

- When tests and assignments are evaluated, girls are judged and congratulated for their form (neat writing, careful presentation, good conduct, work) while boys are judged and congratulated for the content of their work and their performance (skill, intelligence, giftedness, creativity).

- The comments concerning difficulties experienced by girls tend to refer to cognitive considerations and feedback focuses on a need to return to basics and concerns about the pupil’s general comprehension. In the case of boys, these same difficulties are perceived as being more punctual in nature and primarily related to their behaviour.

Observations concerning girls

Interactions with adults and peers

- Girls put more effort into their interpersonal relations.

- Girls enjoy transmitting their knowledge to younger children.

- For girls, their school girlfriends are of great importance and they often talk with them about anything at affects the school environment.

- Girls appreciate the human qualities of their teachers or at least, expect to see those qualities in their teachers. They perceive those qualities positively.

- Girls receive compliments from their teachers as much for their behaviour as for their academic performance: they would appear to be quiet, dynamic, disciplined although sometimes talkative, in accordance with female stereotypes.

- When it comes to homework and lessons, mothers – who are primarily responsible for overseeing these tasks – give their daughters more leeway to organise how they go about doing their work.

- The segregation and stereotypes that girls are subject to encourage them to adopt behaviours of resistance by seeking to build coalitions within their gender category.

- In terms of hobbies, parents direct their daughters primarily towards fine arts and individual sports, since such activities appear to have characteristics (for instance, quiet and artistic talent) that are perceived as being intrinsic to girls.

- Girls are asked to lend a hand more often than boys to tutor students experiencing difficulties or to help the teacher, which reinforces the stereotype of the girl responsible for the care and well-being of others.

Learning styles and relationship with school

- Girls see learning as something that relates to self-actualisation: learning enables them to look to the future and to value themselves.

- Resilience in a school context is stronger with indigenous girls than with indigenous boys (Saint-Amant, 2003).

- They see the benefits of what is being taught and even enjoy subjects they find difficult.

- Girls experience a lot of stress during exam periods.

- Girls believe more strongly that perseverance will guarantee them of a better future.

- Girls prefer to work in teams with other girls, claiming that boys don’t work hard enough.

- Girls are very concerned about their success and this is why they spend as much time as possible in class. They are calmer and less impulsive than boys, and follow rules and instructions more closely.

- The self-esteem of girls who have poor grades suffers: they are convinced their grades will never earn them the recognition of others.

- Girls have higher occupational aspirations than boys: their career choices require more schooling.

Observations concerning boys

Interactions with adults and peers

- Boys who do well and have a positive relationship with school are more likely to be bullied and excluded socially, precisely because they do not fit in with the group culture of boys.

- Similarly, boys who do not like sports or who are not good at sports are rejected by other boys because they don’t correspond to masculine criteria concerning physical performance. In addition and as a result, these boys are subjected to homophobic slurs such as “epitejijewe’k” (boy/person who acts like a little girl / like a sissy) or “kistale’k”.

- Rejection is more common for boys and is often based on male gender stereotypes or transgressions, that is, behaviours deemed female (“epitejijewe’k”).

- Boys do not appreciate a teacher’s authority or teachers who are considered “too tough”. They see them as authoritarian figures who are against pleasure and fun, and not as pedagogues.

- Stereotypes are very common in sports where boys self-evaluate on the basis of their performance or physical strength.

- At recess, boys tend to instigate physical and verbal violence more often.

- When it comes to homework and lessons, mothers – who are primarily responsible for overseeing these tasks – give their sons more guidance than they do their daughters.

- Boys volunteer less often for tasks suggested by their teacher and are more selective: the tasks have to correspond to so-called masculine activities connected to recreation (like bringing in the ball after recess) or ones that require them to display physical strength (like carrying a pile of books).

- Similarly, boys tend to contribute more when performing physical tasks, which reinforces the belief that strength is a masculine quality.

- Boys are quickly introduced by their parents to hobbies that give them the opportunity to express their dynamism and inventiveness; examples include group sports, hunting, fishing and technological activities.

- Adults in school environments give more of their time to boys, who on the whole receive more encouragement, criticism, listening and praise than girls.

- In addition to being asked to answer questions more often, boys are given more complex instructions and their spontaneous interventions earn more responses.

- Teachers pay attention more quickly when boys are turbulent, since they are reputed to be more agitated. Consequently, they notice this behaviour more often, which reinforces their initial beliefs.

Learning styles and relationship with school

- Boys are more likely to have a negative relationship with school; they have no or little liking for school and prefer sports and recreation. For them, school often brings to mind boredom, restrictions and obligations.

- In the case of boys who say they like school, it’s because for them school is primarily a place where they take part in activities. Masculine sociability, sports and recess encourage boys to enjoy school in the short term.

- School work is considered an unpleasant task.

- Boys are not as comfortable at school as girls and are more permeable than the latter to disturbances, to a change in teachers for instance.

- School is less important to

- More boys don’t know what they want to do later. More boys think they’ll do the same thing as their fathers do (in contrast to girls and their mothers) and would like to have jobs in their fields of interest or connected to their favourite recreation activity.

- Boys often overestimate their capacities to resolve the problems presented to them.

- The greater attention given to boys apparently helps them build their self-confidence.

- Boys speak in class more often and more spontaneously in response to questions from teachers, and interrupt in class more often than girls.

- According to a study conducted with Nova Scotian teachers, mi’gmaw boys who get good grades are accused by their peers of trying to be white, to adopt white values (Davison et al., 2004).

References

Brabant, C., Croteau, M., Kistabish, J. et Dumond, M. (2015). « À la recherche d’un modèle d’organisation pédagogique pour la réussite éducative des jeunes et des communautés des Premières Nations du Québec : points de vue d’étudiants en administration scolaire », Revue de la persévérance et de la réussite scolaires chez les Premiers Peuples, Vol. 1, pp. 29-34.

Commission de l’Éducation (2007). Mandat d’initiative : La réussite scolaire des Autochtones – Rapport et recommandations, février 2007, Bibliothèque et archives nationales du Québec, 68 pages.

Canadian Council on Learning (2007). Redefining How Success is Measured in First Nations, Inuit and Métis Learning, Report on Learning in Canada 2007 (Ottawa: 2007). 47 pages.

Canadian Council on Learning (2009). The State of Aboriginal Learning in Canada: A Holistic Approach to Measuring Success, (Ottawa: 2009). 77 pages.

Conseil du statut de la femme (2016). Avis: L’égalité des sexes en milieu scolaire. Québec, Gouvernement du Québec, 154 pages, accessible at : https://www.csf.gouv.qc.ca/wp-content/uploads/avis_egalite_entre_sexes_milieu-scolaire.pdf

Davison, K., Lovell, T., Frank, B. et Vibert, A. (2004). « Boys and Underachievement in the Canadian Context : No Proof for Panic », dans S. Ali, S. Benjamin et M. Mauthner (Eds.), The Politics of Gender and Education : Critical Perspectives (p. 50-64). Palgrave macmillan.

Epiney, J. (2013). (In)égalité filles-garçons à l’école primaire : Regards et représentations des enseignant-es du second cycle en Valais, Lausanne, 211 pages, accessible at : https://www.resonances-vs.ch/images/stories/resonances/2012-2013/mai/md_maspe_johan_epiney_2013.pdf

Femmes autochtones du Québec (2014). « Les femmes autochtones et l’exploitation sexuelle », Consultation du comité interministériel du gouvernement du Québec sur l’exploitation sexuelle, April 3rd, 2014, accessible at : https://www.mmiwg-ffada.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/FAQ-Femmes-autochtones-et-lexploitation-sexuelle-2014.pdf

Gagnon, C. (1999). Pour réussir dès le primaire : filles et garçons face à l’école, Les Éditions du remue-ménage, Montréal, 173 pages.

Girard, J. et Vallet, M. (2015). « La réussite éducative : les solutions au-delà de l’école », Revue de la persévérance et de la réussite scolaires chez les Premiers Peuples, Vol. 1, pp. 26-28.

Saint-Amant, J. (2003). Comment limiter le décrochage scolaire des garçons et des filles ?, article retrieved on June 15th, 2020, at : http://sisyphe.org/article.php3?id_article=446%5D.

Santerre, N. (2015). « Une alliance synergique pour la réussite des étudiants autochtones au Cégep de Baie-Comeau », Revue de la persévérance et de la réussite scolaires chez les Premiers Peuples, Vol. 1, pp. 20-22.

Secrétariat à la condition féminine (2018). « Portail Sans stéréotypes », accessible at : http://www.scf.gouv.qc.ca/sansstereotypes/comment-agir/ce-qui-est-propose/

Sylliboy, J. (2017). Two-spirits: Conceptualization in a L’nuwey Worldview, Mount Saint Vincent University, 113 pages.