Once they’ve started primary school, children already have a fairly advanced understanding of what it means to be a boy or a girl. In fact, by around 5 to 7 years of age, children understand that an individual’s sex remains constant in all circumstances and the same over time, and that it is defined by biology (Boyd and Bee, 2015). Other studies suggest, however, that the construction of gender identity is dynamic and can be reshaped in children later as they develop (Mieeya and Rouyer, 2013). Whatever the case may be, when they enter primary school, children have very often already developed characteristics traditionally associated with their sex as a result of the differentiated socialisation they experienced throughout their early childhood (SCF, 2018).

Development of gender identity

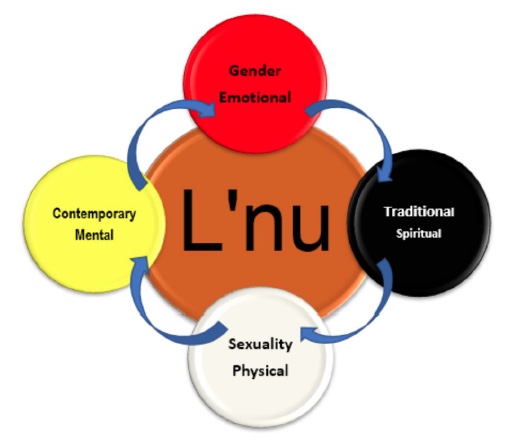

According to a conceptualization by John Robert Sylliboy (2019, p. 106), a two-spirited Mi’gmaq, the identity of a human being (L’nu) has four dimensions (emotional, spiritual, physical and mental) and encompasses both historical traditions and contemporary practices. Therefore, mi’gmaw children develop their gender identity while balancing its spiritual dimension, rooted in cultural traditions, and its mental dimension that reflects contemporary practices.

Gender identity continues to develop throughout early childhood and usually crystallises at around the age of seven, although in some people this can vary and continue to be re-shaped throughout life (Mieeya and Rouyer, 2013). Gender identity is “an individual’s gender experience which may or may not correspond to their biological sex or the one assigned at birth. Consequently, any individual may identify themselves as a man, a woman or somewhere between these two poles, regardless of their biological sex. All people – regardless of sexual orientation – have a gender identity” (LGBT Family Coalition, 2018, p. 2).

Gender identity is developing during early childhood and is usually “set” arounf the age of seven (Mieeya & Rouyer, 2013). This could link to the teachings of the mi’gmaw Elder Murdena Marshall: according to her and other Elders, a significant change is happening in one’s life every seven years.

In many First Nations, people with a gender variant identity are called two-spirits (Sylliboy, 2017). If the definition of the term “two-spirits” changes from one Nation to another, “Albert McLeod defines it as ‘a term used to describe aboriginal people who assume cross- or multiple-gender roles, attributes, dress and attitudes for personal, spiritual, cultural, ceremonial or social reasons.’” (Monkman, 2016). There is no specific word in Mi’gMaq to adequately represent this concept, although studies are undergoing to determine which mi’gmaw expression would represent it best (Sylliboy, 2019).

Consequently, it is possible for children of primary school age to wonder about their gender identity. And this is not necessarily directly tied to the children’s interests (games, clothing, models, etc.). “So it is important to avoid thinking, for instance, that because a boy is interested in a so-called feminine activity, he sees himself as a girl, or vice versa. On the contrary, children commonly adopt behaviours that are socially attributed to the opposite sex and such behaviours have nothing to do with the gender to which a child identifies inwardly” (SCF, 2018). In those cases, it is important to value the child, validate his or her choices and interests even if they vary from the norm and let him or her explore.

Gender stereotypes in elementary school-aged children

According to a study conducted in Québec by the Conseil du statut de la femme (2016), most primary school teachers surveyed fully or somewhat agreed with the following statements:

- Girls do better in French than boys;

- The brains of boys and girls do not work in quite the same way;

- Gender differences are not the result of inequalities between men and women;

- Schools in Québec are not adapted to the needs and specificity of boys;

- Boys need more dynamic and active educational methods; and

- Boys need to move more than girls.

However, these claims are neither based on biological characteristics nor are they scientifically founded. At birth, the brains of boys and girls differ only in reproductive function. Children between 0 and 3 years of age therefore have the same cognitive (intelligence, reasoning, memory, attention, spatial identification) and physical skills (Vidal, cited in Piraud-Rouet, 2017). The differences that develop between girls and boys are attributable to the plasticity of the brain, that is to say, its ability to transform with learning and environment (Piraud-Rouet, 2017). As for the psychological and behavioural differences between sexes, while they tend to increase from childhood to adulthood, they are nearly absent in infants and toddlers (Cossette, 2017).

When children enter primary school, most have already adopted the behaviours expected in children of their sex. Thus, in a study conducted at several primary schools in the Québec City area, “all of the boys had internalised an evaluation model depicting masculinity based on traditional stereotypes. According to these stereotypes, a boy must be sporty, undisciplined, indifferent to academic results and able to defend himself. Boys who refuse to conform to this model are excluded from the group” (Gagnon, 1999, p. 29). Sylliboy recalls that during his childhood, boys from his Reserve that didn’t embrace these stereotypes and acted effeminate were described as epitejijewe’k, a clearly negative term. Young boys were being told “mu’k epitejijewey”, which meant “don’t act like a little girl or don’t act like a sissy” (Sylliboy, 2017, p. 23).

As for girls, several studies show that when merely 7 years old, girls would already like to be thinner: at this age, they can already identify a part of their anatomy that they want to improve (SCF, 2018). As soon as they enter primary school, girls are also less confident and underestimate their competencies (BBC, 2018). However, they appear to be more resistant to female gender stereotypes, particularly if they have better grades (Gagnon, 1999), which is consistent with studies that show a correlation between adherence to gender stereotypes and school leaving (Réseau Réussite Montréal, 2018). In John R. Sylliboy’s mi’gmaw community, young girls who didn’t embrace gender stereotypes were called l’pa’tujewe’k, which translates as “girl/person acting like a boy” (Sylliboy, 2017, p. 24).

Thus, boys and girls seem to adopt behaviours and demonstrate strengths that naturally differ according to sex. But these differences, however, turn out to be the result of differentiated socialisation.

Differentiated socialisation

Although the family, day care centre, toys and books for children are the primary agents responsible for the differentiated socialisation of girls and boys during early childhood, this process continues at primary school: “so the teachers play a key role in this gendered socialisation of pupils by extending what the children have already experienced within their families” (Epiney, 2013, p. 17).