The experience of Mi’gmaq college students is marked by a variety of gender stereotypes resulting from gender-based differentiated socialization and cultural biases derived from a lack of knowledge between Quebec’s indigenous and non-indigenous people (Gauthier, 2015b). In this section, we look at how this socialization influences the students’ connection to school and their learning styles as well as how the teaching staff contribute to differentiated socialization without realizing it.

School Leaving at College: A Gendered Situation

College dropout rates are alarming. For technology programs, for instance, the success rate after six years is only 66% (Breton, 2016). There is also still a gender gap in terms of the graduation rate, which reflects a gendered connection to school.

In the Gaspésie–Îles-de-la-Madeleine administrative region, for the student cohort that entered college in 2009, the graduation rate—students who obtained their DCSs two years after the usual duration of the program—was 61.7% for girls and 50.9% for boys, a difference of 10.8% (Cartojeunes, 2019). In Québec, moreover, this rate has fallen further for girls (from 70.3% to 67.4% over five years) than for boys (57.3% to 56.1%) (Dion-Viens, 2017), all Nations combined. The Cégep de la Gaspésie et des Îles-de-la-Madeleine welcoming very few Mi’gmaq students, we are unable to access data related to their school retention at this level.

The reasons why girls and boys drop out of college are also very different (Roy et al., 2012b):

| For boys | For girls |

|---|---|

| Factors connected to the educational institution | Personal and family-related reasons and difficulties; |

| Attraction of the labour market; | Academic difficulties; and |

| Lack of motivation (or interest) and commitment to their studies; | Too heavy a workload. |

| Role exerted by their social network (friends who want to drop out of school); and | |

| Low importance of academic success in terms of values. |

Lack of motivation and commitment to education are two very important factors in determining student retention, which may explain why more boys drop out (Roy et al., 2012d). In addition, employment opportunities for boys without diplomas are much more interesting than those that exist for girls (Chouinard, Bergeron, Vezeau & Janosz, 2010), traditionally male jobs being better paid than those traditionally reserved for women. However, more girls are able to conciliate work and their studies (Duchaine, 2017) as well as family responsibilities and studies (Santerre, 2015), which might explain why, when they do drop out, they say it’s because their work load is too heavy or they’re having trouble at school.

Finally, it must also be said that sociocultural origin and gender play a role in the number of students enrolled: upon arrival at college, the disparity between young men and young women is even greater for young people from less advantaged sociocultural communities: 30 men for 70 women, when both parents have at best completed their secondary school studies. In contrast, this imbalance is considerably mitigated when the young people come from advantaged communities (53 women for 46 men) (Eckert, 2010, p. 158).

Learning Styles and Relationship With School

Before looking at the differentiated connection to school and learning of Mi’gmaq boys and girls, let’s look at a few context points related to the connection of First Nations to school as an institution. First of all, it is worth repeating that for hundreds of years, amongst Indigenous peoples, teachings have been passed on within the context of the family and the community. School has been implemented just over 50 years ago; First Nations’ educational tradition is then quite young and it clashed in many ways with their traditional lifestyle (Commission de l’éducation, 2007, p. 10). The residential schools, implemented in Quebec between 1934 and 1980, as well as all the colonial system, negatively impacted indigenous people’s relationship with educational institutions (Gauthier, 2015b; Santerre, 2015). Indigenous youth has consequently developed a critical attitude towards the occidental educational institution, considered as a domination and assimilation ideological apparatus (Gauthier, 2015b, p. 16).

We can then say that for a majority of indigenous students, school clashes with their culture (Brabant et al., 2015) and their connection to it is tainted with mistrust. A study conducted at the Baie-Comeau CEGEP offers a concrete example, as researchers explain that Innu students leaving the community face prejudices coming from their own surroundings, especially when they perform well in school. Respondents agree that indigenous students aren’t encouraged to persist in school. Those who do are called “apples”, a comparison meaning they have red skin on the outside, but a white heart on the inside (Gauthier, 2015b, p. 84). Fortunately, Audy and Gauthier (2019) highlight that according to many researchers, young First Nations members’ connection to school and education is the theatre of a profound change and is becoming a lot more positive, less reactive and resistant.

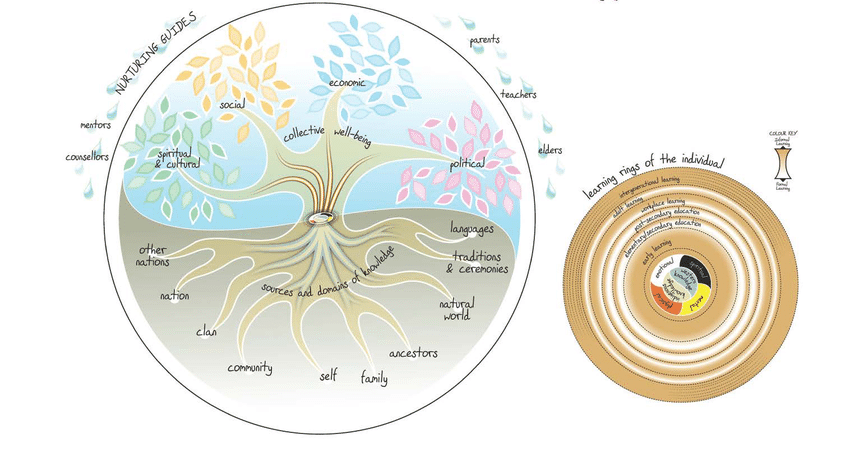

According to the Canadian Council on Learning (2007), learning from an indigenous perspective is holistic and experiential, it is a lifelong process rooted in Aboriginal languages and cultures, it is spiritually oriented, it is a communal activity, involving family, community and Elders and it integrates Aboriginal and Western knowledge.

Perceptions of School Perseverance and Acamedic Success

It is also important to underline a few elements related to the perceptions of school perseverance and academic success amongst First Nations, even though it can vary from one Nation to another and from one person to another. If, in the European-inspired educational system, academic success is measured with grades, it is often the other way round in indigenous communities, where the survival of the culture and the language is equally important (Commission de l’éducation, 2007), where family is a priority (Gauthier, 2015b) and where succeeding means obtaining a diploma, even if it takes longer than what is initially planned in the regular pathway stated in the program they’ve engaged in (Santerre, 2015). For the Innu, for example, academic success is defined by parents, students and teachers more in terms of perseverance and of capacity to put in enough efforts to get passing grades. The notion of perseverance then becomes an important dimension of academic success (Commission de l’éducation, 2007, p. 11). For the Inuit, ancient know-how that supports traditional lifestyles, such as knowing how to survive in tundra, is equally important (Commission de l’éducation, 2007). Within the Innu community of Mashteuiash, it is assumed that academic success is a collective responsibility and that it is by taking into account all dimensions of the Human Being that we achieve good health, a pride feeling and academic success. The Pekuakamiulnuatsh have a global and holistic vision of the present time and the future, and they make sure to foster the spiritual, emotional, mental and physical fulfillment of everyone (Girard & Vallet, 2015, p. 27).

During a panel organized in the context of a symposium on the academic perseverance of First Peoples, young indigenous graduated students shared as follows their perception of academic success and perseverance (Gauthier, 2015a, p. 99): already very proud of being accepted in a graduated program, with all the other steps and efforts that comes with it in their sociocultural context (let’s not forget that they come from very remote communities), their first concern is to adapt progressively to their new student reality. They are not very worried about performing in class and they aren’t traumatized by an eventual failure. In their mind, it isn’t a big deal if it happens, they have the patience to redo the course if necessary.

Therefore, the length of their studies isn’t very important to them, even if failures, considered necessary by many Innu students from the Cégep de Baie-Comeau, are difficult to take, because they sometimes have the impression that non-indigenous teachers and students believe they are not able to succeed because of their indigenous roots. This perception brings some indigenous students to drop out courses or even the whole program they are enrolled in (Gauthier, 2015b, p. 88).

Consequently, when looking at the connection to learning of young Mi’gmaq boys and girls, we have to put aside the accounting view of academic success to adopt a holistic approach (St-Amant, 2003). In that sense, the First Nations Holistic Lifelong Learning Model of the Canadian Council on Learning (2009) is a good example of how the connection to learning of many First Nations members isn’t limited to the educational institution itself, but has to be rooted in the community, to touch on many dimensions of the individual and the society, and has to be formal at certain moments, such as during the post-secondary schooling process, and informal at other times, such as during early childhood.

First Nations Holistic Lifelong Learning Model (Canadian Council on Learning, 2009)

Gender Stereotypes and Learning Styles

Some behaviours, values and characteristics that vary significantly by sex have been targeted by teams conducting research in the education field (Eckert, 2010; Baudoux and Noircent, 1993; Roy, Bouchard and Turcotte, 2012a, 2012b, 2012c) since they are connected to school perseverance:

| Boys... | Girls... |

|---|---|

| Attach more importance to competition; | Attach greater importance to the relational sphere (family, loved ones, friends); |

| Are involved in more physical activities outside college; | Attach more importance to respect; |

| More often deal with their problems alone; | Attach more importance to the effort needed to succeed; |

| Drink more alcohol; | Read books more often; |

| Are involved in more extracurricular activities; | More often feel the workload is too heavy; |

| Comment spontaneously more often; | Spend more time on their studies; |

| Are more mobile in class and take over the area around them; | Attach more importance to academic success and obtaining a college diploma; |

| More often answer questions identified as difficult; | Attach more importance to having a united family; |

| Speak out more often even if they haven’t been asked to do so; | Earn better grades; |

| More often answer questions that have nothing to do with the subject matter; | Attach more importance to having a successful relationship with their partner; |

| Are more unruly and argue more against instructions from teachers; | Consider their teachers’ levels of knowledge to be higher; |

| Interrupt speakers more, tease and push others more, particularly girls; and | Help more, congratulate more and disapprove boys less than the opposite; |

| Consult the teachers at the head of the class more often. | Receive more hostile comments from boys, are criticized more often, are targeted by sexist comments, are assaulted verbally and physically; |

| More often answer closed questions put to the group; | |

| Raise their hand more often without obtaining acknowledgment; and | |

| Ask for more explanations at the end of the class. |

Academic behaviours, values and characteristics according to gender

Noircent and Baudoux (1993, p. 154) also note that in situations where boys and girls are on the same team, tasks are distributed according to gender stereotypes. In addition, the authors mention that it is in the natural science groups that girls are most invisible when it comes to speaking and where they are most often interrupted; in contrast, in social science groups and in groups where they are a minority, they behave more actively. Finally, girls would seem to be quieter in technology classes and in classes that are mostly female or that have male-female parity. Saint-Amant (2003) notices that amongst First Nations, a gap between boys’ and girls’ academic perseverance is also noted, at a point where resilience in school seems to be associated with girls.

These characteristics, observed more frequently in boys and girls, are the outcome of gender-based differentiated socialization built on gender stereotypes. For instance, if boys are expected to be competitive, be more mobile, and occupy more physical and sound space, they will develop by trying to meet these implicit expectations. These stereotypes influence the connection to learning and school differently for boys and girls.

As Baudoux and Noircent (1993, p. 150) point out, the teaching staff, who are very sensitive to issues of equity in education, do not suspect they treat students differently. And yet, this is the case: teachers unconsciously reproduce gender stereotypes through their own interactions with students and because of what they expect of their students. Consequently, not only do they evaluate behaviour differently by gender, they also tend to spot behaviours that are consistent with male or female gender (Baudoux and Noircent, 1993). Here are a few examples.

General observations

- Teachers often ask boys open questions while girls are asked to answer closed or multiple-choice questions.

- In cases where boys and girls get the same poor grades, girls are twice less likely than boys to be considered of concern by their teachers.

- When teachers believe that the assignments they are correcting were submitted by boys, they give higher grades.

- A very well-presented assignment is devalued if the teacher supposes it was produced by a girl and complimented if the teacher thinks it was done by a boy.

- Teachers tend to attribute poor results by boys to a lack of effort; in contrast, when girls do poorly they tend to attribute it to a lack of intellectual skills.

- Boys are more often punished or reprimanded publicly while girls are spoken to briefly, quietly, often unbeknownst to the rest of the class.

- Interactions between teachers and students are stereotyped; domination and separation are used with boys (teachers use the imperative) while girls are spoken to softly and are encouraged to be complicit with their teachers.

- The use of the masculine as the generic pronoun not only discriminates against girls but also renders women and their accomplishments invisible, and causes female students to tend to stay on the sidelines.

- Many stereotypes continue to be depicted in the books and texts used in class; this in itself excludes women from the narrative content.

- Teachers don’t get as close physically to girls as they do to boys when their students ask them questions unless the class is mostly female.

Boys…

- Receive more attention from teachers in terms of approval (congratulations), disapproval, comments or listening than girls;

- Are asked more direct, semi-open, complex or abstract questions;

- Receive more instructions from their teacher prior to beginning an assignment and more encouragement later;

- Are more active and have more educational interactions with their teachers;

- Occupy a greater space in discussions centred on the topic, initiate such discussions, answer questions, comment spontaneously and direct lesson content;

- Receive more individual help from teachers, who scrutinize their responses more closely for potential learning difficulties;

- Are better known to their teachers, who remember their first names more quickly, are more concerned with their success and see them more quickly as individuals;

- Are criticized more often for incorrect answers or even for not answering; and

- Even when boys and girls exhibit the same reprehensible behaviours, boys are reprimanded more often.

Girls…

- Participate less in class discussions and are more likely to be invisible;

- Not only receive fewer instructions, but teachers take the initiative to complete tasks the girls should have performed; their independence is not encouraged as much;

- Are part of an undifferentiated group for a long time; questions tend to be put to the group and not to individual girls;

- Do not object to doing boring jobs; and

- Fail to obtain answers to their questions more often than boys.

These differentiated attitudes on the part of students and staff towards male and female students are unconscious, but nevertheless very much present. They are shaped by differentiated socialization, anchored in the gender stereotypes experienced by both teachers and students throughout their lives. We must first become aware of these stereotypes and then work to deconstruct them, through self-reflection and by working to this end with students.

Drop out-related factors: Anchored in stereotypes?

While strong adherence to gender stereotypes is associated with higher dropout rates, some other school dropout factors are gender-specific and require appropriate actions.

Transition from Secondary school to college: Gendered trajectories

Girls are more sensitive to transitions such as the transition from primary school to secondary school; a difficult transition can lead to academic difficulties, dwindling interest in school and, ultimately, dropping out of school. As for the transition from secondary school to college, studies have shown that the difficulties associated with this transition would seem to be more apparent in boys (Rivière et al., 1997; Tremblay et al., 2006, cited in Roy et al., 2012b). Indeed, their first college term may be a moment of vulnerability for some boys, both academically and personally. The boys most at risk at college apparently feel more out of it and find it more difficult to organize themselves, be independent and manage their schedules. Consequences: it would seem they more easily fall behind and repeatedly fail (Roy et al., 2012d, p. 9).

In addition to having to deal with this transition as well, young indigenous students can also experience a cultural shock when they leave their community for the CEGEP: a transition time is often needed because of the marked differences between these two environments and because of the break marked with their social network. Adelman, Taylor and Nelson (2010, cited in Joncas & Lavoie, 2015, p. 18) highlight the fact that leaving one’s indigenous community to pursue post-secondary studies brings a fundamental stress that can lead to dropping out of school. Gauthier (2015b, p. 13) echoes these thoughts, stating that the shock is quite brutal when they get to post-secondary studies because they no longer have a familiar environment and they become suddenly culturally a minority. Dropouts and failures are frequent in this context, but studies have shown that institutions that are sensitive to their reality and that implement welcoming and supporting programs greatly foster post-secondary perseverance of young First Nations students.

Gauthier (2015b, p. 93) also notes that the deficient preparation to post-secondary education has a major impact on First Nations students when they reach college because they suddenly face an accelerated rate compared to what they’ve been used to. In addition, they have to adjust their working methods and respect stricter deadlines. They now have to plan their tasks over 15 weeks instead of a full school year staggered over 10 months. They also have difficulty adapting to the requirements of many teachers and to assume their responsibilities in regard to handing in assignments and be present in class.

This being said, since the degree to which students adapt to college life is a key element in the pursuit of their studies, those having more difficulty dealing with the stress of this transition are more likely to drop out later (Meunier-Dubé and Marcotte, 2016). Anxiety and school-related stress are much more prevalent in girls than in boys (Dion-Viens, 2017; Roy et al., 2012a).

Mental Health

A number of mental health-related psychological factors, including depression and anxiety, affect school perseverance in young people differently depending on their gender.

Researchers have observed that young people between the ages of 15 and 18, that is, at ages just before or concordant with entry into college, depression rates increase significantly for both genders and rates of depression amongst girls are up to twice as high as those observed amongst boys (Meunier-Dubé et Marcotte, 2016). In Gaspésie–Îles-de-la-Madeleine, anxiety and depression are the most common mental health disorders and are more prevalent in women. They are significantly more likely than men (30% versus 19%) to experience a high level of psychological distress. And it is amongst young people between the ages of 15 and 24 that this proportion is highest, at 42% (Direction de santé publique Gaspésie–Îles-de-la-Madeleine, 2017).

This being said, the presence of depressive symptoms, including psychological distress, would seem to be a major factor for predicting the risk of dropping out, and play a role in the difficulties young people may have in adapting to college. Other symptoms of depression include difficulty concentrating, which could adversely affect to a considerable degree the ability to function of students and their academic performance. For students experiencing depression, it would appear that there is an alteration in some of their cognitive functions, such as those involved in memory and attention. These aspects highlight the difficulties depressed students may encounter when faced with the new academic requirements of the college environment. In addition, many depressed students feel they have a future in which they will not be able to do the job they want. Loss of interest in their usual activities is another sign of depression; a number of depressed students experience a loss of interest for fields of study or for activities they previously enjoyed, which can adversely affect the development of their identity and keep them from choosing a career, with the attendant serious consequences in terms of staying at school (Meunier-Dubé and Marcotte, 2016).

Coupled with the increasing depression rates in young people, more than a third of college students in Québec, particularly girls, must deal with anxiety (Dion-Viens, 2017). This anxiety is not unrelated to the stress resulting from academic pressure, which is two to three times more prevalent in girls (Roy et al., 2012c, p. 151). In Gaspésie–Îles-de-la-Madeleine, about 11% of young people between the ages of 15 and 24 estimates that most of their days are fairly stressful, even extremely stressful, with women tending to be more stressed (Direction de santé publique Gaspésie–Îles-de-la-Madeleine, 2017).

Thus, to encourage girls to stay at school, it is critical to take into consideration the fact that they face a higher risk in terms of mental health (school-related stress, anxiety and depression), pay particular attention to the related signs in girls and adjust our actions accordingly since they are more likely to experience their connection to school with a degree of stress and anxiety (Doray, Langlois, Robitaille, Chenard & Aboumrad, 2009).

Parenting

Some college students, whether returning to college or arriving there from secondary school, must conciliate their role as parents with their studies and sometimes even with a job. Since women are still, even today, responsible for most of the work associated with household tasks and child rearing (Couturier and Posca, 2014), this conciliation can be more difficult for female students and can affect their school perseverance, particularly in the case of single-parent families (in GÎM, 74.3% are women (Statistics Canada, 2016)).

At the Cégep de Baie-Comeau, indigenous students are generally adults returning to college and this group is mainly made up of single mothers (Santerre, 2015, p. 22). However, from an indigenous point of view, Gauthier (2015a, p. 98) notes that if, in first place, this situation obviously doesn’t help with staying in school, especially since young indigenous women often have their first child during teenage, it seems that it becomes a powerful motivation generator when they come back to school and a key element of academic perseverance. This brings the author to say that even if it is obviously astutely to make young mothers aware of the risks and consequences of early pregnancy, as much energy should be put in offering them parental support that would allow them to stay in school while being a young mother, one not necessarily going against the other.

Academic and Occupational Guidance

The occupational segregation between men and women observed in Gaspésie-Îles-de-la-Madeleine is strongly influenced by gender stereotypes. This segregation also exists in the occupational choices made by students in the region, particularly with regard to secondary school vocational programs and college technology programs. Data for technology programs at the Cégep de la Gaspésie et des Îles-de-la-Madeleine (CGÎM) shows female enrolment consistent with each sector’s traditional nature, either predominantly male or predominantly female (CGÎM, 2018). Gender stereotypes would also seem to influence the students’ career choices.

Generally, this situation is also observed in pre-university programs with particular profiles. According to a study conducted at the Cégep de Sainte-Foy, girls are proportionally more numerous in programs such as medical technology and nursing, social science-related technology (social work, special education, early childhood education), the arts and literature program and social science—helping relationships and social action profile. As for boys, they tend to enroll more often, proportionally speaking, in natural science, in computer technology and in social science—organization and management profile (Roy et al., 2012b, p. 41).

Students arriving at college have not necessarily made firm career choices yet and this is more often the case for boys. So it would be appropriate to accompany them from the time they arrive to help them consider all kinds of occupations, regardless of gender stereotypes.

References

Audy, N. et Gauthier, R. (2019). Introduction. Revue de la persévérance et de la réussite scolaires chez les Premiers Peuples, 3, 6-7.

Baudoux, C. et Noircent, A. (1993). Rapports sociaux de sexe dans les classes du collégial québécois [Gender relations in Quebec’s college classrooms], Revue canadienne de l’éducation, 18(2), 150-167. http://journals.sfu.ca/cje/index.php/cje-rce/article/view/2654/1962

Boutin, N. (2011). L’effet du genre sur l’indécision vocationnelle et les parcours scolaire : l’intégration des garçons aux études collégiales [The effect of gender on career decision difficulties and academic pathway: The integration of boys to college studies] [mémoire de maîtrise, Université Laval]. CorpusUL. https://corpus.ulaval.ca/jspui/handle/20.500.11794/22721

Brabant, C., Croteau, M., Kistabish, J. et Dumond, M. (2015). À la recherche d’un modèle d’organisation pédagogique pour la réussite éducative des jeunes et des communautés des Premières Nations du Québec : points de vue d’étudiants en administration scolaire [Looking for an educational organization model supporting youth and Quebec’s First Nations communities’ academic success], Revue de la persévérance et de la réussite scolaires chez les Premiers Peuples, 1, 29-34.

Breton, B. (2016, 18 mars). Décrocher du cégep et de l’université [Dropping out from CEGEP and university], Le Soleil. https://www.lesoleil.com/opinions/brigitte-breton/decrocher-du-cegep-et-de-luniversite-8e3730f7eac5306a87114ce6edd6ce9d

Canadian Council on Learning (2007). Redefining How Success is Measured in First Nations, Inuit and Métis Learning. https://www.afn.ca/uploads/files/education/5._2007_redefining_how_success_is_measured_en.pdf

Canadian Council on Learning (2009). The State of Aboriginal Learning in Canada: A Holistic Approach to Measuring Success. https://www.afn.ca/uploads/files/education2/state_of_aboriginal_learning_in_canada-final_report,_ccl,_2009.pdf

Cartojeunes (2019). Parcours scolaires à l’enseignement collégial [Educational pathways in college], Cartojeunes. http://cartojeunes.ca/carte/parcours-scolaires-a-enseignement-collegial

Cégep de la Gaspésie et des Îles-de-la-Madeleine. (2018). Compilation spéciale réalisée par Isabelle Vilchenon.

Chouinard, R., Bergeron, J., Vezeau, C. et Janosz, M., (2010). Motivation et adaptation psychosociale des élèves du secondaire selon la localisation socioéconomique de leur école [Motivation and psychosocial adaptation of high school students in relation to the socioeconomic location of their school], Revue des sciences de l’éducation, 36(2), 321-342 https://www.erudit.org/fr/revues/rse/2010-v36-n2-rse3909/044480ar.pdf

Commission de l’Éducation (2007). Mandat d’initiative : La réussite scolaire des Autochtones — Rapport et recommandations, février 2007 [Initiative mandate: Academic success of First Nations – Report and recommendations, February 2007], Bibliothèque et archives nationales du Québec. http://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/1762627

Couturier, E. et Posca, J. (2014). Tâches domestiques : encore loin d’un partage équitable [Domestic chores: still far from an equal sharing]. Note socioéconomique, Institut de recherches et d’informations socioéconomiques. https://cdn.iris-recherche.qc.ca/uploads/publication/file/14-01239-IRIS-Notes-Taches-domestiques_WEB.pdf

Dion-Viens, D. (2017, 2 juin). Le décrochage en hausse au cégep : Un expert tire la sonnette d’alarme [Dropout in rise at college level: an expert is sounding the alarm]. Journal de Québec. https://www.journaldequebec.com/2017/06/02/le-decrochage-en-hausse-au-cegep

Direction de santé publique Gaspésie–Îles-de-la-Madeleine. (2017). La santé et le bien-être de la population de la Gaspésie–Îles-de-la-Madeleine — Édition 2017 [Health and well-being of the Gaspésie–Îles-de-la-Madeleine’s population – 2017 Éditions]. https://www.cisss-gaspesie.gouv.qc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/La_sante%CC%81_et_le_bien-e%CC%82tre_de_la_population_de_la_Gaspe%CC%81sie-I%CC%82les-de-la-Madeleine_-_E%CC%81dition_2017.pdf

Doray, P., Langlois, Y., Robitaille, A., Chenard, P. et Aboumrad, M. (2009). Étudier au cégep : les parcours scolaires dans l’enseignement technique [Studying in CEGEP: educational pathways in technical teaching]. Centre interuniversitaire de recherche sur la science et la technologie. https://depot.erudit.org/bitstream/004068dd/1/2009_04.pdf

Duchaine, G. (2017, 24 janvier). La diplomation en recul chez les filles [Girls diplomation is receding]. La Presse. http://plus.lapresse.ca/screens/b45190c1-bc7d-47c5-9c9c-4e44d3c7cc38__7C__T_~rJqYWRu8L.html

Eckert, H. (2010). Le cégep et la démocratisation de l’école au Québec, au regard des appartenances socioculturelles et de genre [CEGEP and democratization of education in Québec in light of sociocultural and gender identities], Revue des sciences de l’éducation, 36(1), 149-168. https://www.erudit.org/fr/revues/rse/2010-v36-n1-rse3870/043990ar/

Gauthier, R. (2015a). Ce que persévérer veut dire pour de jeunes autochtones inscrits aux études supérieures [What persisting means for young indigenous graduated students], Revue de la persévérance et de la réussite scolaires chez les Premiers Peuples, 1, 96-99.

Gauthier, R. (2015b). L’étudiant autochtone et les études supérieures : regards croisés au sein des institutions [The indigenous student and post-secondary studies: comparative views within institutions]. Cégep de Baie-Comeau, Université du Québec à Chicoutimi. https://www.capres.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Chantier3_Rapportfinal13fe%cc%81vrier-2.pdf

Girard, J. et Vallet, M. (2015). La réussite éducative : les solutions au-delà de l’école [Academic success: solutions beyond school], Revue de la persévérance et de la réussite scolaires chez les Premiers Peuples, 1, 26-28.

Institut de la statistique du Québec. (2020). Répartition de la population de 25 à 64 ans selon le plus haut niveau de scolarité atteint, la région administrative, l’âge et le sexe [Distribution of the population aged 25 to 64 years old according to the highest level of education reached, the administrative region, age and gender], Québec, 1990 à 2019, Gouvernement du Québec. https://bdso.gouv.qc.ca/pls/ken/ken213_afich_tabl.page_tabl?p_iden_tran=REPEROIY0BN32-19325031028a.,A(&p_lang=1&p_m_o=ISQ&p_id_ss_domn=824&p_id_raprt=3012#tri_tertr=50040016500000000&tri_sexe=10&tri_age=365&tri_stat=8404

Joncas, J. et Lavoie, C. (2015). Pour une meilleure compréhension de l’expérience scolaire atypique de persévérants universitaires des Premières Nations à l’UQAC [For a better understanding of the atypical educational experience of persistent First Nations university students at UQAC], Revue de la persévérance et de la réussite scolaires chez les Premiers Peuples, 1, 17-19.

Lavell Harvard, D. M. (2011). The Power of Silence and the Price of Success: Academic Achievement as Transformational Resistance for Aboriginal Women [PhD thesis, The University of Western Ontario]. Scholarship@Western. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1179&context=etd

Meunier-Dubé, A. et Marcotte, D. (2016). Les difficultés de la transition secondaire-collégiale : quand la dépression s’en mêle [Difficulties around the high school-college transition: when depression is involved], Réseau d’information pour la réussite éducative. http://rire.ctreq.qc.ca/les-difficultes-de-la-transition-secondaire-collegiale-quand-la-depression-sen-mele/

Roy, J., Bouchard, J. et Turcotte, M. (2012a). Filles et garçons au collégial : des univers parallèles ? [Girls and boys in college: parallel universes?]. Pédagogie collégiale, 25(2), 34-40.

Roy, J., Bouchard, J. et Turcotte, M. (2012b). Identité et abandon scolaire selon le genre en milieu collégial [Identity and school drop out according to gender in college environment]. Cégep de Sainte-Foy/Équipe Masculinités et Société. https://cdc.qc.ca/parea/788248-roy-bouchard-turquotte-identite-abandon-scolaire-genre-ste-foy-PAREA-2012.pdf

Roy, J., Bouchard, J. et Turcotte, M. (2012c). La construction identitaire des garçons et la réussite au cégep [Boys’ identity construction and success in CEGEP], L’identité et la construction de soi chez les garçons et les hommes, 58(1), 55-67. https://www.erudit.org/fr/revues/ss/2012-v58-n1-ss0144/1010439ar.pdf

Roy, J., Bouchard, J. et Turcotte, M. (2012d). La réussite scolaire selon le genre en milieu collégial — Une enquête par questionnaire [Academic success and gender in college environment – a questionnaire survey]. Cégep de Sainte-Foy/Équipe Masculinités et Société. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Gilles_Tremblay/publication/52000371_La_reussite_scolaire_selon_le_genre_en_milieu_collegial_-_Une_enquete_par_questionnaire/links/0deec52015d6ce7b6e000000/La-reussite-scolaire-selon-le-genre-en-milieu-collegial-Une-enquete-par-questionnaire.pdf

Saint-Amant, J. (2003). Comment limiter le décrochage scolaire des garçons et des filles ? [How to prevent boys and girls from dropping out of school?], Sisyphe. http://sisyphe.org/article.php3?id_article=446%5D.

Santerre, N. (2015). Une alliance synergique pour la réussite des étudiants autochtones au Cégep de Baie-Comeau [A synergistic alliance to promote First Nations students’ success in Cégep de Baie-Comeau]. Revue de la persévérance et de la réussite scolaires chez les Premiers Peuples, 1, 20-22.

Statistiques Canada. (2011). Le niveau de scolarité des peuples autochtones au Canada [Level of education amongst First Nations in Canada]. https://central.bac-lac.gc.ca/.item?id=CS99-012-2011-3-3-fra&op=pdf&app=Library

Statistiques Canada. (2018). Profil du recensement, Recensement de 2016 [Census profile – 2016 Census], Gaspésie–Îles-de-la-Madeleine. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/prof/details/page.cfm?Lang=F&Geo1=ER&Code1=2410&Geo2=PR&Code2=24&Data=Count&SearchText=Gaspesie–Iles-de-la-Madeleine&SearchType=Begins&SearchPR=01&B1=All&GeoLevel=PR&GeoCode=2410&TABID=1

Toulouse, P. (2016). What Matters In Indigenous Education: Implementing A Vision Committed To Holism, Diversity And Engagement. Dans Measuring What Matters, People For Education. Toronto: March, 2016.